The world turned upside down: Brexit, seven years on.

Seven years ago, this is what I thought Brexit would mean. I think I got it right.

Seven years ago, the morning after the June 23, 2016 referendum in the UK on whether or not to leave the European Union, I wrote an article and posted it on my old blog (now defunct). Today, on the anniversary of the vote, I went back to my digital archive to reread it. As a historian who often tries to use history to project what the future might be like, I'm the first to admit that I sometimes get it wrong. But reading over my 2016 Brexit article I was struck by how much of what I said has proven to be true.

What 52% of the British people voted for on June 23, 2016 has now been put into practice. The UK is out of the EU. After chewing up three prime ministers in a row (Cameron, May and Johnson), the slow-motion disaster of Brexit has made the UK markedly poorer, meaner and more exclusionary. Few wounds that a country has inflicted upon itself will, I think, prove to be as deep as Brexit. And even now in 2023 the pain continues.

Below, in its entirety, is my Brexit article from June 24, 2016. The reference to "The World Turned Upside Down" involves the 1781 Battle of Yorktown, in which the British Army surrendered to U.S. commander George Washington.

Like millions of people around the world, I went to bed last night (June 23, 2016) in a state of shock and anxiety after spending the evening watching the tallies from the British EU referendum come in. Although polls said it'd be close, I just couldn't believe that Britain would do it. Perhaps I was naïve. I did not really think Britain would vote to leave the European Union, which would have the effect of isolating it economically and weakening what's left. We all know what happened: "Leave" pulled off a narrow victory. This morning, Prime Minister David Cameron announced he'll be resigning. World financial markets are still in a tailspin. And I don't think it's an exaggeration to say that we now live in a totally different, and much more uncertain, world.

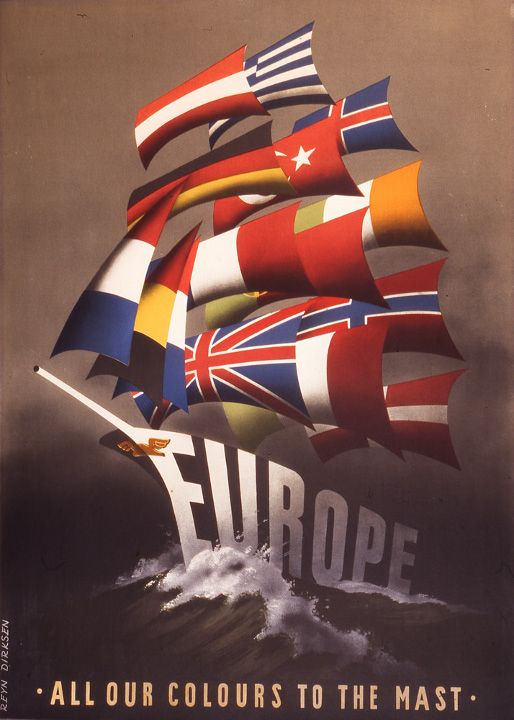

I am not British and I couldn't vote. But that the "Remain" option was better seemed so self-evident to me that I couldn't imagine a majority of the British public not seeing it. To me, Brexit represents not just a new economic or political policy. It's a fundamental historical shift in a very dangerous direction. It essentially repudiates the geopolitical goals that Western policymakers, in Britain, the U.S. and elsewhere, have pursued since the end of World War II. While I understand the reasons why many voters supported it, I think Brexit destroys the idea of an economic and political integration of Europe and injects a dangerous dose of uncertainty into world politics. It also represents a blow to our collective efforts to address climate change, which may be the most serious of the legacies of this very unfortunate vote.

Many commentators today are troubled especially by the way Brexit was sold to the British public. Many supporters of "Leave," like the fulsome xenophobe Nigel Farage of the far right-wing UKIP party, talked it up as a way to staunch immigration of Muslims to the UK, especially from Syria. Right-wing politicians are usually hostile to any scheme involving multinational integration, so the immigrant issue was a convenient stalking horse to tear down the EU that they oppose on principle. I don't mean to suggest that all "Leave" voters were motivated by these issues, but disturbingly many were. The resonance of authoritarian political messages in Britain is a troubling sign coming at the same time as another right-wing authoritarian figure, Donald Trump, is getting uncomfortably close to the U.S. presidency. Both Trump and "Leave" have fed off the discontent of working class people and the older generation. A stunning 75% of Britons under 25 voted "Remain." They will have to live the longest with--and eventually fix--the consequences of the disastrous vote their elders forced upon them.

One of the most serious problems British millennials will have to fix is climate change. Brexit hobbles their efforts to do so. Britain is already committed, under the Paris Agreement, to large carbon emissions reductions. Those will be costly. But without the EU to help shoulder all member nations' costs of emissions reductions, a go-it-alone Britain will have to shoulder that burden on its own. And if Brexit means a contraction of the British economy, which is certain to occur and will get much worse if Scotland and Northern Ireland split off (which at this point seems likely), they'll be paying this bill from a significantly smaller wallet. This doesn't take into consideration all the help, financial and otherwise, that Britain might have provided other EU members in reaching their reduction targets or taking other actions to combat climate change. A significantly weakened EU will be a much less capable partner for the U.S., China and other big economies in tackling climate change. Thus, all of us around the world may indirectly pay for the choice of the "Leave" voters, in the form of damage from superstorms, sea level rise, droughts and other effects of climate change. Today I asked a British friend of mine, a strong "Leave" supporter, if he had thought about this while deciding how to vote. He admitted he hadn't.

Most ominously, I fear what Brexit will do to the stability of Europe. I learned in high school history class that the idea of European political and economic integration, which has been pursued in one form or another since the end of World War II, was the reason why there would never again be cycles of destructive wars in Europe as we saw in every century from the 17th to the 20th. This was the whole point of the Marshall Plan, in which President Truman sought to rebuild Western European economies, partially with U.S. money, to inoculate them from falling victim to Soviet Communism. In the post-Cold War era integration, now in the explicit form of the EU, was supposed to counterbalance Russia, China and the U.S. Britain is the largest and richest member of the EU. What if what's left of the EU, even including Scotland and a unified Ireland, becomes an economic battleground between its two largest remaining members, Germany and France? What if other right-wing parties in individual countries take Britain's example and try to leave too? The Netherlands is already contemplating their own referendum. What's left in Europe if the EU totally or even partially disintegrates?

The UK is not my country, but as a citizen of the world that will be affected by it, I do have a stake. In my view Brexit represents a dangerous change. European political and economic cooperation is one of those bedrocks of the modern world that has, until recently, seemed unassailable. It seemed that way to me all the way up until last night. Now add the European Union to the growing pile of formerly stable institutions that have become broken or badly dysfunctional during this century: the United Nations, neutered by the U.S. invasion of Iraq; the global economy, badly mauled by the Great Recession of 2008; the U.S. political system, now in slow-motion meltdown largely as a result of the radicalization of the Republican Party. We can't count on anything anymore. The more institutions crack and crumble, the closer we get to some large-scale catastrophic failure. And don't forget that climate change is going to get much, much worse before it gets any better.

It is said that, as the British army of Lord Cornwallis surrendered to General Washington at Yorktown in the last battle of the Revolutionary War in 1781, the British fife and drum corps played a song called "The World Turned Upside Down." That song hasn't been played much in the past 200 years, but it deserves another go-round. With Brexit the British have surrendered again, this time to forces that we should have left in the past: nationalist fervor, xenophobia, generational antagonism, isolationism and the old instability that made Europe a charnel-house for centuries. I think the Brexit vote will go down as one of the greatest mistakes of the modern world, what the late historian Barbara Tuchman would have called "the march of folly." I really hope I'm wrong about that. The people of Britain had better hope so too.

The Value Proposition

Why should you be reading this blog, or receiving it as a newsletter? This is why.

☕ This is where I normally put my Ko-fi link. Don't buy me a coffee this week--order my new history book The 50 Most Important Things in History instead for the same price!

🎓 Like learning? Find out what courses I’m currently offering at my website.

📽 More the visual type? Here is my YouTube channel with tons of free history videos.

Comments ()