The last thing Lincoln saw: the story of "Our American Cousin."

The play Lincoln was watching at the time of his assassination has an interesting history of its own.

One hundred and fifty-eight years ago tonight, April 14, 1865, which like today (2023) was also a Friday, was the most famous "night out" in American history. On that evening Abraham Lincoln, President of the United States, went to Ford's Theater with his wife and some other guests which included Henry Rathbone, a U.S. Army major, and his fiancé Clara Harris, to see a comedy play, Our American Cousin. This was the first entertainment Lincoln felt he had time for in a long time--the Civil War had ended the previous Sunday with Lee's surrender at Appomattox Court House in Virginia. Of course, we all know what happened to Lincoln at the play that terrible night. The assassination is the final scene (or almost the final scene) in almost every movie made about Lincoln and the almost-final chapter in every biography of the Great Emancipator; historians often spend the last page or so describing the funeral train that took Lincoln's body on a somber pilgrimage back to Springfield, Illinois. This article is not about that story. It's about the play the Lincolns were watching when he was shot by John Wilkes Booth, which rarely gets any treatment on its own in Lincoln assassination lore.

Our American Cousin was a light comedy written by playwright Tom Taylor, who was British. The comedic subject of the play concerns social, linguistic and cultural differences between Americans and Britons. In a nutshell, the play is about an American, Asa Trenchard, who is distantly related to some British socialites who have recently fallen on hard times. Asa is left some property in the will of one of his British relatives, and goes to England to claim the estate. Hilarity ensues, or at least, hilarity by 1860s standards.

Tom Taylor, an upper-class Briton himself, was a stalwart of the English theater scene beginning in the 1840s. He wrote over 100 plays in his career, many of them light farces like Our American Cousin. This particular play was first performed in New York City in October 1858. Although not the star of the show, the real draw was British actor Edward Sothern, who portrayed the supporting role of Lord Dundreary, a bumbling British nobleman. Audiences howled in laughter at Sothern's performance which became more elaborate, with extensive ad-libs, as the successful run of the play continued. Lord Dundreary proved so successful a character that he recurred in numerous other plays of the time, eventually becoming something of a stock character. Sothern was eventually typecast in these sort of roles. Oddly enough, although he made the play famous, Sothern was not playing the role of Dundreary that night.

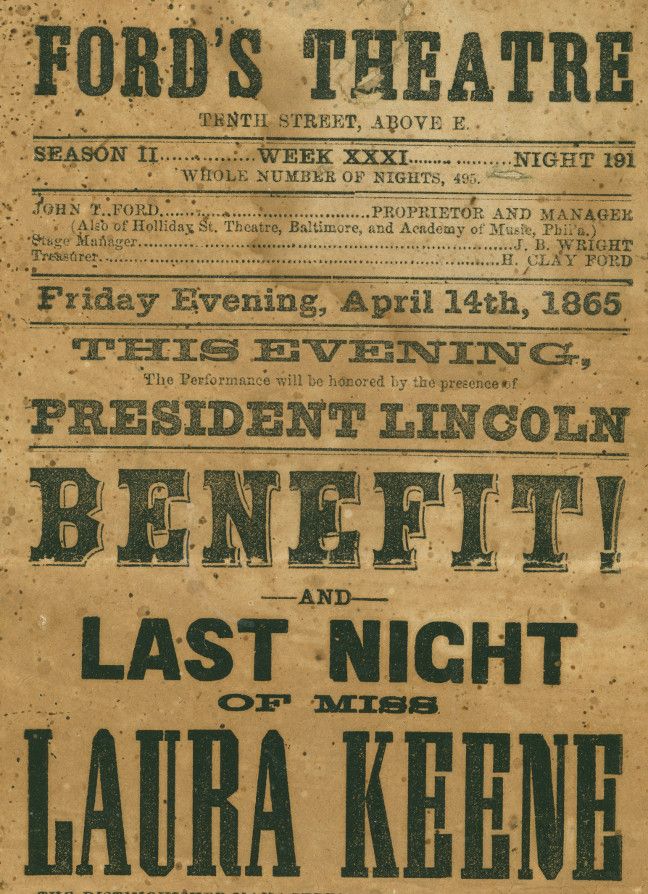

The real star of Our American Cousin was Laura Keene. Notice, in the copy of the handbill promoting the performance, that Keene gets top billing in terms of typeface size, even more than Lincoln himself. Also British-born, Keene moved to the United States in 1853 and not only acted but became a theater manager and impresario. It was at her theater, owned by her and stocked with her troupe, where Our American Cousin premiered and became a hit in 1858. The ownership and licensing of the play was a source of conflict and eventually litigation. In November 1858 a rival company began performing it in Philadelphia. In a twist of irony, the co-owner of the Philadelphia production of the play was one John Sleeper Clarke, who, a few months later, married the sister of actor John Wilkes Booth--the eventual assassin of Lincoln.

Keene regarded herself as the true owner of the play, and she and her troupe later took the show on the road. One of the venues for the traveling show was a grand new theater built in Washington, D.C. by John T. Ford, an actor. Ford initially built his theater in 1862 but it burned down. He reconstructed it on a grander scale; the second 1863 incarnation was the building Lincoln visited that fateful night. One of the people who hung around Ford's Theater, and kept a mailbox there, was John Wilkes Booth.

Booth, as is well-known, was the spearhead of an extensive, months-long conspiracy to decapitate the Union government by kidnapping or killing several of its top officials, Lincoln being only one. That plot eventually morphed into a series of assassinations, including Secretary of State William Seward and Vice-President Andrew Johnson, that would theoretically take place simultaneously. Booth cooked up this plot, considerably different than the original version, basically the day-of. No one at the theater knew Lincoln was supposed to be coming until late that afternoon. The handbills printed up to advertise the final show of Our American Cousin made no mention of him, but as soon as the exhibitors found out the President was coming a new batch was printed. Booth heard from Ford's brother than Lincoln was expected to attend.

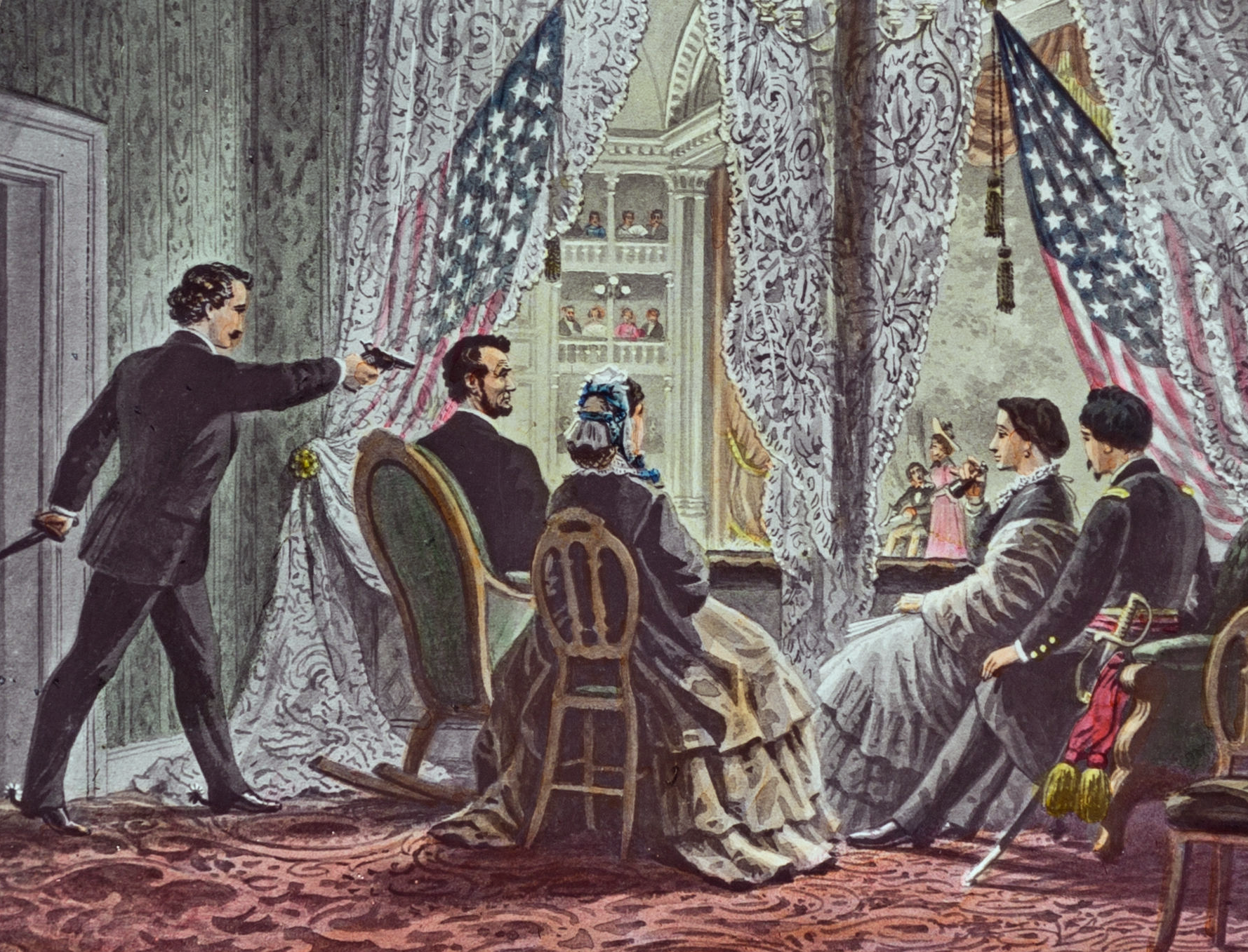

Booth knew the play well, though he had never acted in it. His familiarity with the dialogue was, in fact, a key element of the assassination. He waited until the third and final act, when a line by Asa Trenchard, played by Harry Hawk, was expected to get a big laugh: "Don't know the manners of good society, eh? Well, I guess I know enough to turn you inside out, old gal--you sockdologizing old man-trap!" When the audience laughed, Booth, who was at that moment sneaking up behind Lincoln's chair, pulled the trigger of his Derringer. Contrary to what you see and hear in almost every recreation of the assassination, the sound of the shot was not audible to most of the audience. That was the point of waiting until the big laugh in Act 3.

You would think that, as traumatic as the assassination was to the nation, Our American Cousin would be tainted forever by its association with the act. Actually, you'd be wrong. Our American Cousin continued to be performed even after April 1865. Even more astoundingly, John Sleeper Clarke, who as you recall was the brother-in-law of Lincoln's assassin, mounted yet another production of the play at the Winter Garden Theater in New York in September 1865. Keene sued him again. The case wound its way through the courts for some time, but after protracted litigation Keene ultimately prevailed. Clarke gave up on Our American Cousin and went to England, which was probably for the best. Laura Keene died in 1873.

Our American Cousin continues to be performed once in a while, mainly as a result of its association with the Lincoln assassination. Various adaptations have been made of it, such as an opera in 2008 that incorporates the assassination into the story. This play, which would have faded into total obscurity if not for the accident of its association with the event, is now indelibly intertwined with it.

In a curious twist of fate, 98 years later another piece of visual entertainment became part of the story of a presidential assassination. In 1865 John Wilkes Booth shot Lincoln in a theater and was eventually apprehended (killed, actually) in a warehouse; in 1963, Lee Harvey Oswald, the assassin of John F. Kennedy, shot Kennedy from a warehouse and was apprehended in a theater. On the afternoon of November 22, 1963, Oswald hid from police in the Texas Theater in Dallas after shooting Kennedy and Dallas police officer J.D. Tippitt. The cops caught up with him there. The movie being shown at that time was called War Is Hell, but this film has none of the notoriety that Our American Cousin gained from the Lincoln assassination.

Lincoln, of course, never lived to the end of that performance. But we do know what he thought of Our American Cousin. He'd seen it before. Apparently he was not a fan of it, which makes one wonder why he agreed to sit through it again. Perhaps he relished the opportunity to get out of the White House after the long nightmare of the Civil War. And it was supposed to be a comedy, though its meta-story is undoubtedly a tragedy.

The Value Proposition

Why should you be reading this blog, or receiving it as a newsletter? This is why.

☕ If you appreciate what I do, buy me a virtual coffee from time-to-time to support my work. I know it seems small, but it truly helps.

📖 You could also buy my newest book.

🎓 Like learning? Find out what courses I’m currently offering at my website.

📽 More the visual type? Here is my YouTube channel with tons of free history videos.

Comments ()