Speak no evil: the Satanic Verses affair, 34 years on.

The controversy over one of the world's most infamous books still leaves a lot of questions unanswered.

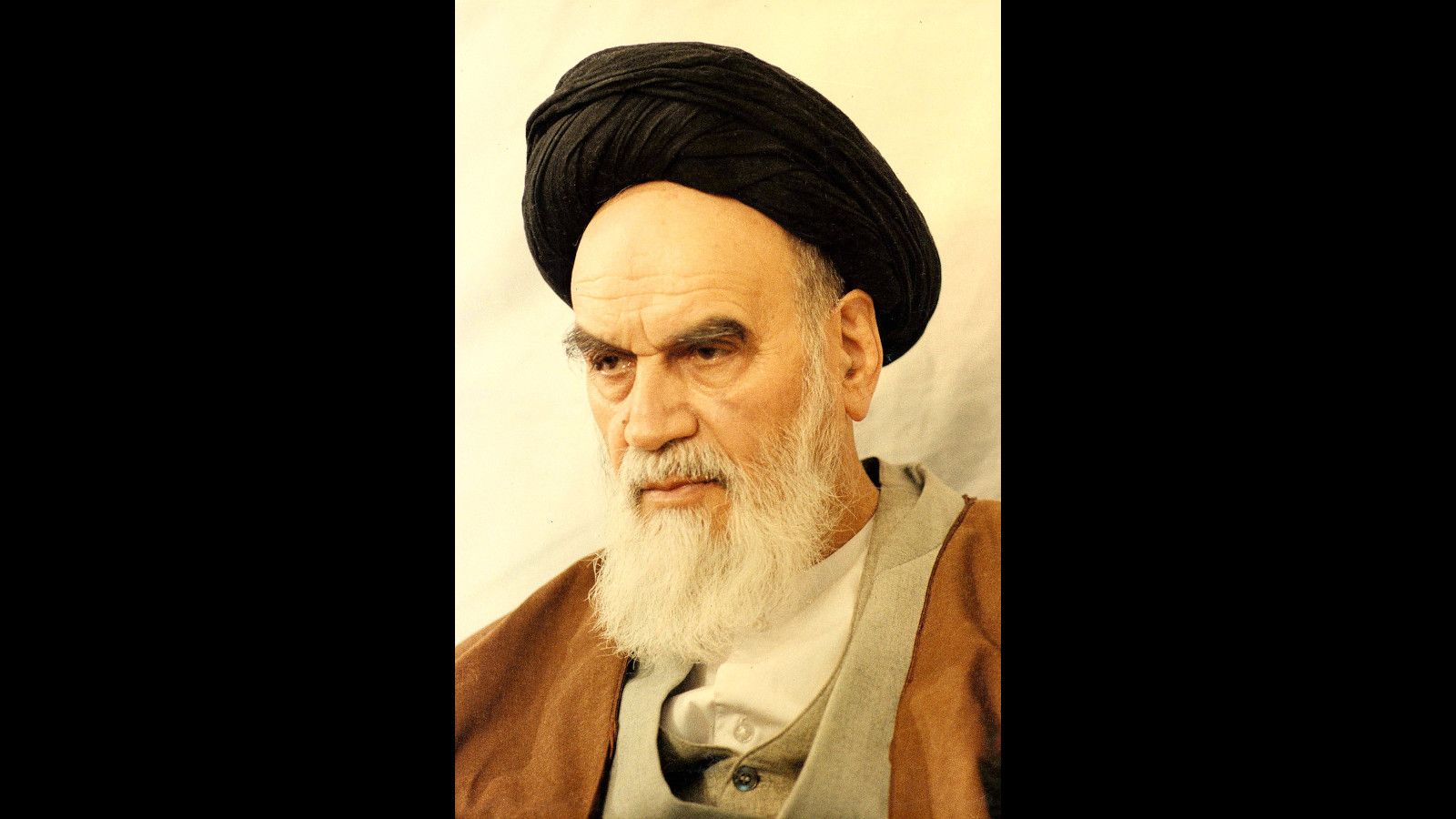

Thirty-four years ago today, on February 14, 1989, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, the spiritual and political leader of Iran, issued a fatwa--a form of holy commandment--calling for the murder of British author Salman Rushdie, author of the bizarre postmodern novel The Satanic Verses which was perceived in the Muslim world as insulting the prophet Muhammad. The infamous controversy over this book and the reaction of the Islamic world to it is so complicated, involving not just religion but geopolitics, philosophy, law and even the cultural role of publishing and literature that it’s almost impossible to fathom today. The fatwa and its repercussions have been referred to as one of the most important events in literary history in the second half of the 20th century.

Lest you think it's ancient history, less than a year ago, in August 2022, a knife-wielding madman attacked Rushdie at a speaking event in Chautauqua, New York, intending to carry out the decades-old fatwa. Rushdie survived, but had he not he would have joined the body count of victims whose deaths were related to his book, such as Hitoshi Igarashi, translator of The Satanic Verses into Japanese, murdered in a stabbing attack in 1991, or the 12 Indians killed, mostly by police, in a violent riot against the book in Mumbai. There have also been numerous other attempted murders and bombings, including a terrorist who blew himself up in August 1989 with a bomb intended for Rushdie.

In the West in 1989, The Satanic Verses affair played out in the press and public discourse as a rather simple-minded morality play. Rushdie, a British citizen, was targeted by a foreign religious leader who had no jurisdiction over him for exercising free speech rights, generally protected by most liberal democracies. This was contrasted with the medieval barbarism of Khomeini's reactionary theocratic state seeking to avenge what looked to most non-Muslim westerners as a trivial slight against the prophet Muhammad, who had been dead for more than 1300 years. That was how the press framed it. In reality The Satanic Verses affair was far more complicated than that. Proof positive that more was at work here than met the eye: almost no one involved in the controversy actually read Rushdie's book, which is a confusing mishmash of magical realism, sexual fantasy and cultural references mined mostly from India's complicated postcolonial relationship with Britain. I read it and most of it went over my head. But then again I'm not Muslim, Indian or British, and being in one or more of those categories is a virtual prerequisite for even finding Rushdie's turgid prose marginally comprehensible. Like most media controversies, The Satanic Verses was a screen on which a pre-scripted shadow play was projected, both by Khomeini himself and the western press who went bonkers over the fatwa.

There were problems with the fatwa and the interpretation, treated as monolithic in the West, that The Satanic Verses was a mortal sin against Islam. Some Islamic scholars argued that Khomeini had no religious authority, even under the rules of sharia, to issue the fatwa; in 1998 the government of Iran said it no longer advocated Rushdie’s murder, although its treatment of the edict has always been something of a wink-wink, nudge-nudge type of thing. Some political observers even questioned whether the fatwa had that much to do with the treatment of Islam and Muhammad in the book. There is a passage in the novel that reportedly depicts Khomeini personally, and he may have been insulted, or, he might have been trying to steal the news cycle away from the Soviet withdrawal from Afghanistan, which happened the next day. Khomeini was old and decrepit in 1989 and he died only a few months later, leaving the Iranian government with the convenient excuse that the fatwa could not be rescinded except by the person who issued it. The anger that The Satanic Verses stoked among Muslims was undoubtedly genuine, but it seems unlikely that Khomeini selected the book as a target because he was trying to police Western discourse about the prophet Muhammad for its own sake, which is what the Western press seemed to take for granted. Khomeini was as craven and conniving a politician as any Beltway lobbyist. You can't take anything he did or said at face value.

There were also problems with the morality-play Western press version of the event which held freedom of expression as a sacred shibboleth universally held, and relished the fatwa as a remarkably clear and frontal assault against it. A few months before The Satanic Verses thing erupted, fundamentalist Christians in the United States and Europe went on the warpath at the release of Martin Scorsese's picture The Last Temptation of Christ, adapted from Nilos Kazantzakis's 1955 novel (itself controversial at that time). In Paris, a cinema showing the film was blown up by a terrorist bomb. The Last Temptation controversies were frequently brought up as whataboutist comparisons to the Satanic Verses brouhaha. In the internet and social media age, "freeze peach" as a concept has become weaponized, often wielded by right-wing ideologues to suppress liberal voices they don't like or used as a cudgel by so-called "free speech absolutists," especially in the tech world. Indeed, freedom of expression is not universally protected in the West. Many European countries criminalize Holocaust denial. Antivaxx propaganda is widely seen, correctly so, as a threat to public health. There's a difference between government censorship and moderation in private fora such as social media platforms, but that distinction is often lost when people start arguing about speech controversies, especially when somebody inevitably begins whining about "cancel culture."

One thing that strikes me about The Satanic Verses affair, 34 years on, is how impossible it would be today--though not for the reasons you might expect. Rushdie himself, who sometimes lives in hiding and sometimes not, who has alternately struck apologetic and defiant notes in response to the affair, said in the 2010s that The Satanic Verses couldn't be published in modern times because no one would be willing to court the controversy. Well, duh. That's sort of like saying that no one would be willing to build a hydrogen-filled airship today because no one wants to repeat the Hindenburg disaster. There's a difference between prudence and cowardice. The real reason The Satanic Verses thing couldn't happen today is that practitioners of postmodern literary fiction, disseminated by big publishing houses and their works celebrated as literary events of great importance, simply don't have the power to move the culture that they did back in 1988. Rushdie came from an intellectual and literary tradition, popular in the decades after World War II, where learned writers turned out tomes that satirized the absurdities of the modern world in sardonic prose and mocked the conventions of fiction that had characterized the literary world before that time. Think Thomas Pynchon, Vladimir Nabokov and their ilk. Rushdie, in my view, was a rather junior varsity player on this team. The aim he took at sacred cows in The Satanic Verses was something similar to the way crude 1980s black metal bands wore upside-down crosses and pretended to worship Satan. He was trolling for a reaction.

Consider this: if Rushdie had not been a Booker Prize winner (for his 1981 novel Midnight's Children) and a member of the Royal Society of Literature, would Khomeini have given a hoot in hell about what he wrote? Consider further: could Rushdie even be published today by a major house, without those preexisting credentials? The publishing world has been atomized, by Amazon and the e-reader, into a multiverse of tiny niche interests, and since Oprah Winfrey folded her show you can no longer get on her book club list by lying about having been a Holocaust survivor or a drug addict. The literary world as it existed when The Satanic Verses came out is as dead as Khomeini himself. That's not to say that blasphemy controversies don't or can't erupt today, but it seems like a religious leader bruising for a culture war fight would today look elsewhere than a British writer with little name recognition beyond the New York Times Review of Books.

Yet the controversy remains. Though he is 75 now, the events of last August prove that the chances of Salman Rushdie's life ending at the hands of someone trying to carry out the fatwa, the 34-year-old proclamation of an imam who died in the last century, are very much higher than zero. We should know enough now about the implications of free expression, censorship, religious tolerance and media manipulation to see the Satanic Verses affair as more than the simplistic morality play that it was presented as in 1989. Sadly, I'm not sure we have really moved on as far as we should have. The story of The Satanic Verses remains unfinished.

The Value Proposition

Why should you be reading this blog, or receiving it as a newsletter? This is why.

☕ If you appreciate what I do, buy me a virtual coffee from time-to-time to support my work. I know it seems small, but it truly helps.

📖 You could also buy my newest book. No religious authorities want me dead for writing it.

🎓 Like learning? Find out what courses I’m currently offering at my website.

📽 More the visual type? Here is my YouTube channel with tons of free history videos.

Comments ()