LinkedIn, the bleakest social network: An anatomy of its failure.

Why is LinkedIn so horrible? It goes even beyond the conceptual failure of most social media sites.

Last night, after a decade or so, I nuked my LinkedIn profile. I’ve been souring on it for a long time, and have done little with it in months except to sign in and check it occasionally, but yesterday I decided it was time for it finally to die. I’ve gradually retreated from a lot of social media in the past few years. I quit Twitter/X the day it was bought by you-know-who in 2022, and I barely look at Facebook anymore. But, thinking about it, I think you can make an argument that of all the major social networks, LinkedIn is in many ways the cruelest, bleakest and most insidious of them all. It’s worth considering how this hell site, of which I was once a pretty heavy user, reached the point of critical failure. It’s more than just the failure of social media in general. There was something uniquely nihilistic and horrible about LinkedIn, and I don’t think I’m alone in that judgment. Here, for what it’s worth, is my experience.

If you spend any time on a social network you can quickly figure out what the basic “pitch” was, when it was a wee startup that some Silicon Valley bros—Lee Hoffman and Eric Ly, in this case, in 2003—were shopping around to venture capitalists. Obviously the basic utility of LinkedIn was supposed to be to facilitate business networking connections. That’s certainly that I thought when I joined. But I eventually came to realize that “networking” or “professional development” isn’t really what LinkedIn is about. As I browsed a feed full of posts about climate change and the latest crimes of our insane President appended with tomes of bickering comments, interspersed among promoted posts (advertisements) for investment opportunities and planet-killing AI apps, motivational pap from Gary Vaynerchuk and the waif-like eyes of jobless 20-somethings with forest-green “OPEN TO WORK” rings around their heads, I began to feel a deep sense of cynicism about what I was doing there.

I’m not naïve. I knew long ago that my eyeballs and the people I know, in reality and in cyberspace, were long ago commoditized for the benefit of LinkedIn’s shareholders. But I bought into the supposed value proposition, that lending these aspects of myself to LinkedIn was a fair tradeoff for what it, and the people on it, could do for me. Now I’m not so sure that the value proposition pencils out. In fact, I’m not sure it ever existed in the first place. I was just deluding myself.

I joined when I was still working on my Ph.D., after I’d already spent 12 years practicing commercial real estate law. I joined for the same reason everyone does: to “network” and meet people who might prove professionally useful. I’d originally been gun-shy about it because of the explosively enraging emails that LinkedIn spammed the world with in the 2013-14 period (“You have not responded to Jack Spratt’s LinkedIn request!”) by hijacking everyone’s Outlook contacts, an abuse for which they were sued. Two years or so after that died down I signed up, but didn’t make much use of the platform until I again found myself in the private sector, post-Ph.D., attempting to make a living with an unwieldy hybrid of law-plus-consulting specifically relating to climate change. In 2018 and ‘19 I truly began to lean into it, seeking to connect with people in the climate change community and also with academics and historians. For a while, before the pandemic, I had a dedicated half-hour a day set aside for browsing and cultivating LinkedIn connections.

For a while, it seemed to work. In 2019 I made a connection there with a guy working on a climate change project that looked promising, and I did some consulting work for him. So yes, I did make money as a result of being on LinkedIn. The next year, just before the lockdown hit, I secured another climate-related consulting project that ended up paying well. I occasionally wrote or posted articles that gained significant traction and drove some traffic to my website and eventually the Substack blog that I had before I started the Garden. My bubble of connections grew steadily. The daily half-hour I spent on the site seemed to be paying dividends.

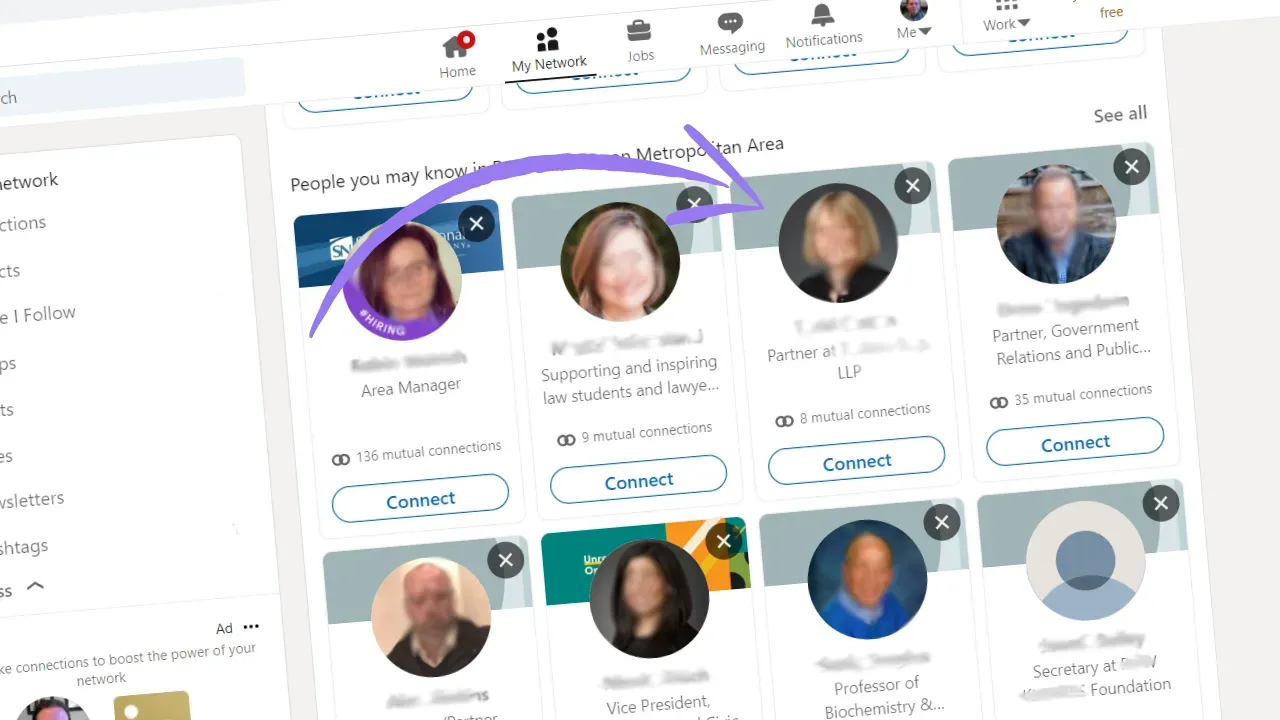

There were a few ugly moments, of course, and some frustrations. Posting anything on social media about global warming brings deniers crawling out of the woodwork like the cockroaches they are, and the anti-climate trolls on LinkedIn seemed especially vituperative. Also, I noticed that LinkedIn’s algorithm could never really figure out who I was or what I did. It assumed that my primary professional identity was as a lawyer. I know this because literally every single time I clicked on the My Network tab, in the “People You May Know” section it suggested that I connect with a lawyer I once knew—I’ll call her “Tessa Orbach” (not her real name)—who was at the first law firm I worked at as an associate in 1998. I did not practice in the same area as Ms. Orbach, I never directly worked with her and did not know her socially. But even after clicking the X to decline the suggestion, it would never take more than two subsequent visits to the Network tab before Tessa Orbach would pop up again. She’s still at the same firm, 27 years later, now senior partner—and LinkedIn still thinks she’s a hot connection for me. And, whenever I would click on the site, I’d see an ad up top saying, “Are you a lawyer? New cases in your area!” This persisted long after I ceased practicing law and even removed references to law practice in my profile. LinkedIn suggested Tessa Orbach as a connection the last time I clicked on the connections tab. To the bitter end it still thought I was a lawyer. To LinkedIn, human beings do not exist—only job titles do. Context is beyond its capability to analyze.

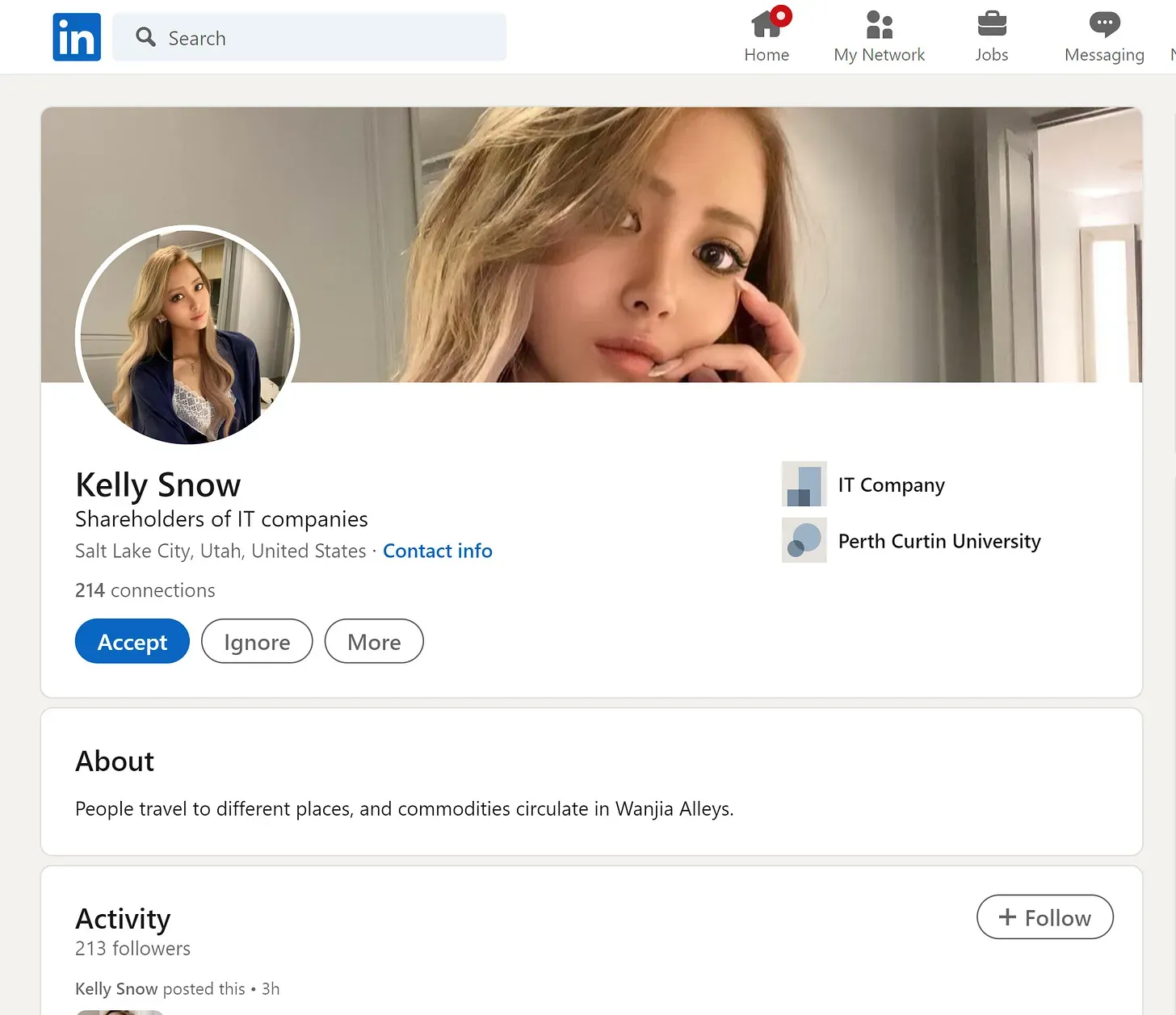

My first real trouble on the platform came in the summer of 2022. I received a connection request from a person, a woman from Pakistan, who judging from her profile appeared to be an academic and totally legit. We had several connections in common. As sometimes happens, she sent me a message thanking me for accepting her connection request. Then I received another message from her, in broken English, to the effect of, “I so lonely, what I would really like to be do is to find a nice man! I know you not come to find romance on LinkedIn but if you would be to explore our feelings...” It was a dating scam. I flagged the message and clicked a button to report it, and the user, as inappropriate. Within 10 minutes, I received an automated reply from LinkedIn stating that the message did not violate LinkedIn’s Terms of Service. Say what? I had a lengthy go-round via email with one of LinkedIn’s “Member Safety and Recovery Consultants” before he finally, and quite reluctantly, conceded that romance scamming was not permitted on their platform—but he was unable or unwilling to explain why the messages and profile I reported were allowed to remain. In fact, he blamed me for the incident. He said I should never have accepted the request.

Then I started getting connection requests from financial advisers. Most of them looked the same: well-meaning white guys usually in their 30s with perfectly-sculpted hair, smiles and suit collars practically gleaming in their profile pics, working for companies with words like “Assurance” and “Fiduciary” in their names. All of these men were quite nice, sending me messages professing to share my concern over global warming or complimenting me on one of my historical videos on YouTube. But after two messages they would invariably ask to have a Zoom call with me to discuss my financial future. It got to the point where, if I received any message from a financial adviser, I would say, “I’m happy to connect, but I’m not looking for financial planning services and do not wish to discuss my finances.” Not a single one replied after that. It turns out they weren’t too interested in talking to me about global warming or my history videos after all.

Again, annoying, but relatively minor in the scheme of things. In late 2021 and early 2022—I was still doing a lot of work in the field of climate change, before it became too depressing—I had several articles on global warming which I posted on LinkedIn go viral. I did reach a lot of people, and the vast majority were supportive and positive. The deniers spewed their usual vitriol, which I expected. With the exception of the deniers, I had no problem with how the individual people I was reaching were reacting to me, but I was starting to feel uncomfortable with how LinkedIn itself was reacting to me. I started getting a lot of connection requests, overwhelmingly from Europeans, working in various sustainability and climate-adjacent fields. Although the vast majority were legit and obviously good people, some were not. One turned out to be a cryptocurrency shill, and another was trying to recruit users to another social network. (No, not Othrys; that happened later). I started getting suggestions to join groups and sign up for newsletters, mostly again sustainability-related. Although the algorithm continued in its stubborn delusion that I was still a practicing lawyer, I started seeing a lot more green-ringed “OPEN TO WORK” 20-somethings whose profiles said they were in sustainability jobs, or seeking them. Because it does not recognize human beings, only job titles, LinkedIn assumes that if you have anything to do with climate change, you must be a sustainability consultant.

Then it struck me: LinkedIn had recognized that I had value. To it. A lot of people were reading my stuff. A lot of people wanted to have me in their networks, for whatever reasons. But the reasons why these things might be desirable, for me, and for my work in history and climate change, were not aligned with why they were desirable for LinkedIn. I want more people to know and understand history. I want more people to be prepared for global warming-related chaos. LinkedIn doesn’t give a damn about any of that. It’s not a value proposition: “I’ll help you achieve your goals, if you help me achieve mine.” It’s instead predation combined with indifference: “Give me what I want to help me make money. If you get something out of the bargain, great. If not, I couldn’t care less.”

The problem is that the purpose of LinkedIn is not to help me “network professionally.” Its purpose isn’t to help me find an audience, or to help those young unemployed sustainability consultants find jobs in their field. Its purpose is to make money for its shareholders. It’s the same problem that Facebook has, and that all social media has. Facebook’s sole and primary purpose is to make Mark Zuckerberg rich. The benefit these networks supposedly provide to us, which is often said as being a means to “connect,” is entirely incidental, a sales job, a reason why you should buy. If they could eliminate that function and still have it make money for shareholders, they’d do that. Facebook sought to commoditize personal relationships. LinkedIn sought to commoditize professional ones. Both companies are essentially cannibalistic, and neither understand the relationships they’re consuming like pellets of fuel. They’re eating us, at home and at work, and pretending to give us benefits so we’ll continue to let them eat us.

LinkedIn failed, but not because it didn’t deliver on the value proposition that I thought I was entering into when I joined in 2015. It failed because that value proposition only ever existed in my mind. A business relationship is, at its core, a sort of negotiation. I have X and want Y; you have Y and want X. To make a successful transaction with you, I have to care that you will actually receive my X in exchange for your Y that I want. LinkedIn wants my X, and it’s happy if I think I’m getting Y out of the deal, but it has no interest in whether I really do. It just wants X, which in this case is my eyeballs, the people I know, and my ability to get others I don’t know to connect with me. Technology can’t fix it. A faster, smarter algorithm can’t fix it. Policing scammers can’t fix it. In order to have value, it actually has to care, and it doesn’t, can’t, won’t, and never will.

Not long before I wrote the first draft of this article I got a connection request which was obviously another romance scammer. It’s pictured above. The profile was laughably false and the picture a hot Asian woman posing in lacy lingerie, probably stolen from a modeling or clothing site. This time I didn’t even bother reporting it. Not only does LinkedIn not care, but it’s clear that romance scammers trolling for marks and financial advisers hustling for clients are its bread and butter. It won’t jeopardize those income streams to better itself, or to help me have “a better experience.” It doesn’t give a damn what kind of experience I have and it never did. It just wants to eat me and, by extension if you know me, it wants to eat you. You cannot negotiate with someone who’s totally indifferent to what you want or need. It’s a hell site, a wasteland of toxicity dressed up like legitimate commerce. Connection declined. I don’t know LinkedIn.

The Value Proposition

Why should you be reading this blog, or receiving it as a newsletter? This is why.

☕ If you appreciate what I do, buy me a virtual coffee from time-to-time to support my work. I know it seems small, but it truly helps.

📖 You could also buy my newest book.

🎓 Like learning? Find out what courses I’m currently offering at my website.

📽 More the visual type? Here is my YouTube channel with tons of free history videos.

Comments ()