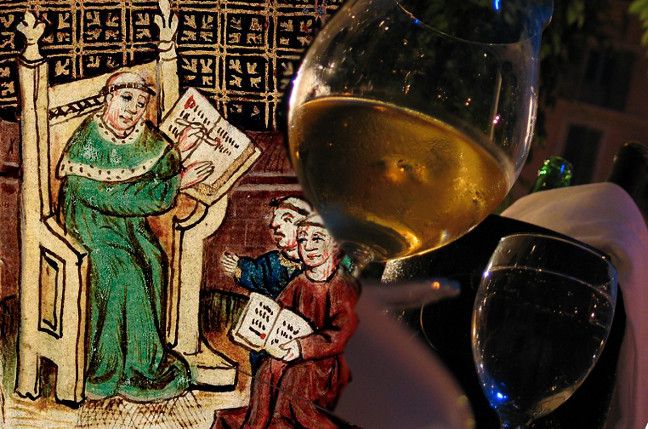

It started with a bad glass of wine: the St. Scholastica Day riots.

The amazing story of how a single glass of wine led to a violent riot and a watershed moment in English history.

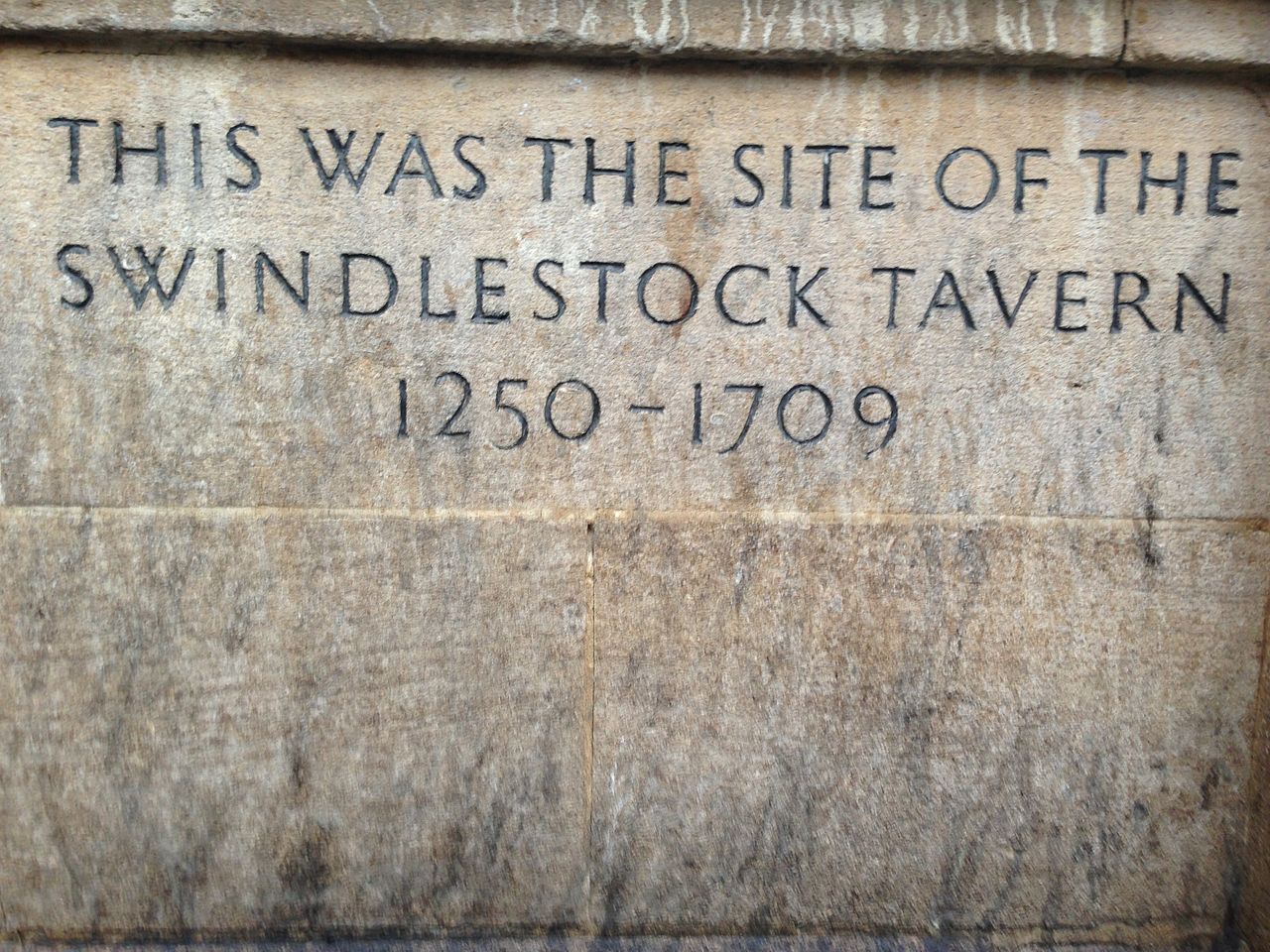

Six hundred and sixty-eight years ago today, on February 10, 1355, two Oxford University students, Walter Spryngeheuse and Roger de Chesterfield, went down to a local pub, called the Swindlestock Tavern, for a drink. This was not unusual for university students either in the Middle Ages or in our own time, but something untoward happened at the pub that evening. Spryngeheuse and de Chesterfield didn't care for the wine served to them by the tavern keeper, John Croidon. They complained and demanded better drinks. Croidon got snippy. The students threw their glasses of wine in Croidon's face, then beat him up and fled the tavern.

The altercation escalated. Croidon enlisted the help of his family and friends, and a mob marched on Oxford. The mayor of the town, John de Bereford, called upon the Chancellor of Oxford, John Charlton, to bring the troublemaking students to account. But Spryngeheuse and de Chesterfield's friends rallied to their defense and a full-scale brawl began between the Oxford students and the people of Oxford town. The altercation at Swindlestock Tavern ignited three days of bloody riots which left 93 people--63 students and 30 local townspeople--pushing up daisies.

To understand exactly what happened during that winter, you have to understand that medieval universities were very different than they are now. Scholars were akin to a religious order, and when a university took up residence in a town, like Oxford, their chancellor negotiated favorable terms on their behalf for lodging, food and other aspects of their support and daily life. This was necessary because in the Middle Ages most scholars were foreigners to the places where they ended up studying and had little understanding of their local surroundings. Because they were a special order, medieval scholars were usually exempt from the laws of the localities where they lived, instead being accountable to the rules of the university. Some local townspeople in the university towns deeply resented this. They saw scholars as effete, arrogant snobs, thumbing their noses at the community and refusing to abide by local rules. However, these communities often needed universities and the money they brought in for their economic livelihood--something that still happens today.

The riots of 1355 were far from the first round of violent altercations between Oxford university students and local townspeople. Indeed the mishigas at Swindlestock Tavern seems to have been a breaking point after decades of strife. This kind of thing is known by historians as "town and gown" controversies. Because the scholars were not subject to local laws, they could get away with outright crimes that would have landed them in jail (sorry, gaol in England) anywhere else. In 1209 a local woman was killed and two students blamed for her murder. The townsfolk lynched the students. It happened again in 1298, when a student was lynched after being blamed for the murder of a local. Coroners in medieval England--they were investigators and crown officials, not medical professionals--held inquests into no less than a dozen killings during the 13th century involving people suspected to have been murdered by university scholars. More often than not, crown officials took the side of the scholars, further incensing local populations. This sort of resentment was smoldering in the background the night Spryngeheuse and de Chesterfield went out drinking.

The St. Scholastica Day Riots fit the pattern of previous incidents. Admittedly it sounds like the Oxford students who started the fight at Swindlestock Tavern were clearly out of line. But not only were the students not punished, but after King Edward III intervened, he ended up punishing the people of Oxford town, levying stiff fines and commanding the mayor and other officials to march in shame through the streets. Astonishingly, the fines Oxford town was commanded to pay to the university remained in force, and were regularly collected, until 1825. This could not have made the local people look very charitably on the university or upon intellectuals in general.

There may also have been other tensions at work here. In 1355 Britain was still reeling from the Black Death, the horrible disease that ravaged the world less than a decade before. Massive social, economic, political and environmental upheavals were going on, and the conflict between Oxford scholars and poor townsfolk may have been a flash point of a larger process of change, adaptation and coping with the aftermath of a disaster so massive that it's almost unimaginable to us today.

History evidently does not record what was wrong with the wine John Croidon served to the students. Maybe it was a bad vintage? Or perhaps Spryngeheuse and de Chesterfield, like Paul Giamatti's character in the film Sideways, had an irrational prejudice against merlot?

The Value Proposition

Why should you be reading this blog, or receiving it as a newsletter? This is why.

☕ If you appreciate what I do, buy me a virtual coffee from time-to-time to support my work. I know it seems small, but it truly helps.

📖 You could also buy my newest book.

🎓 Like learning? Find out what courses I’m currently offering at my website.

📽 More the visual type? Here is my YouTube channel with tons of free history videos.

Comments ()