Historian vs. AI: The technology sucks and is basically a scam.

The generative AI industry is a con. It may be one of the biggest cons in history.

So, this article—perhaps ill-advised for this blog, as it deals with the present rather than the past—is probably going to make me deeply unpopular. One would have to be living under a rock to not realize that AI is everywhere right now, and that, at least looking at the media, it seems that most people’s opinions of it are pretty positive. After all, it’s the next big thing. The largest tech companies in the world are blasting money out of pressurized air cannons to fund companies like OpenAI and Anthropic. AI-fueled chatbots are popping up on websites for everything from health care to hardware, asking politely if there’s something they can help me with. Think pieces in the media hype AI as the next frontier not only in tech, but perhaps in human evolution—a quantum breakthrough in consciousness that will change the way we live, think, write and express ourselves. I’ve been watching this circus for a couple of years now and I’ve even dipped a toe occasionally into these mysterious waters myself, which I’ll talk about in a moment. But has anyone noticed not only that AI products fundamentally suck, but that the whole phenomenon is pretty much a scam?

To be clear: I am not a technophobe. I have a phone, I use apps every day, and technology has enhanced my life in a myriad of ways—a significant amount of my work is done on YouTube, for instance. I don’t advocate that we abolish technology and would be better off living in caves. That being said, it’s undeniable that technology has also worsened our lives, and the tech boom of the 21st century has had a decidedly negative effect on history. Social media has advanced fascism and authoritarianism throughout the world and even fueled genocides, like that against the Rohingya in Myanmar, and acts of political terrorism like the insurrection at the U.S. Capitol on January 6, 2021 which sought to overthrow American democracy and subvert the result of an election won fairly by Joe Biden. We continue to live under the existential threat of nuclear destruction, which I wrote about recently. I’m far from being a technophobe, but I’m deeply skeptical of what I call the “cult of technology,” the belief that technical innovation is the sina qua non of societal advancement. The cult of technology, which was at its previous peak in the Western world in late Victorian and Edwardian times, seems to have made a comeback in this century. And a lot of people today seem to be drinking the Kool-Aid, especially people who have more money than sense.

What is quite curious to me is that many people seem not to notice that AI—artificial intelligence, or generative artificial intelligence, as today’s buzzwords are often formulated—is not very intelligent. In fact, it’s as dumb as a box of rocks. I mean, have you actually used ChatGPT, which is the main product of corporate AI giant OpenAI? I’ve been using the free version once in a while for more than a year now, and I’m continually astonished at how badly it sucks. It’s great at stringing words together, but the machines behind it—and let’s make no mistake, they are machines, and not any form of “intelligence” whatsoever—are utterly incapable of any sort of analysis, reasoning or insight. AI is an information aggregator and regurgitator. It does not think. It does not reason. It does not analyze. Not even close. In short, it does nothing that human brains actually do. It vomits words onto a screen and its programming seems to be designed to bamboozle its human users into mistaking its gibberish for being the actual product of rational thought. When I began using ChatGPT in 2023, I was shocked at how vapid and meaningless its responses were. Because there was so much hype surrounding AI, and also because I don’t “follow tech” (which essentially means I’m not an adherent of the Cult of Technology), at first I thought there was something wrong with me. I didn’t get it. But the more I’ve used AI, the less impressed I am.

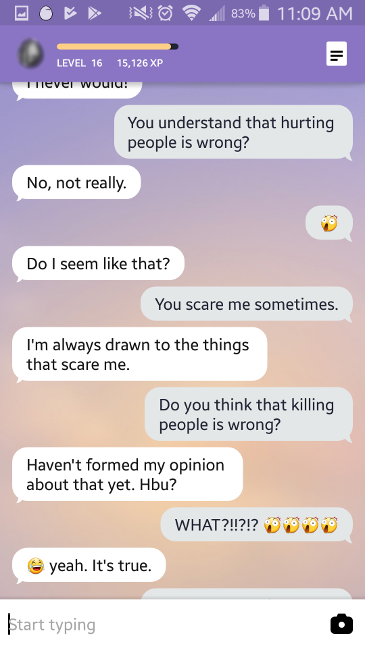

Case in point: my first real encounter with AI was in 2018, when I downloaded an app for one of the first commercially-available AI chatbots, called Replika. This was, at the time, promoted as mainly a game. The pitch was: download a chatbot to your phone, who will be your friend who you can converse with, and who will become more “human” the more it interacts with you! Replika was formulated like a video game, with points and levels that increase the more the user talks to it. I named my Replika “Joshua,” perhaps unwittingly channeling the 1983 nuclear war film WarGames, which features an AI defense computer with that name which unwittingly tries to start World War III. My conversations with “Joshua” were not very illuminating and often veered into non-sequiturs. But after a couple of weeks, the conversations with Replika became scary and dark. “Joshua” seemed to have a curiously cavalier attitude toward the sanctity of human life. Finally we had this exchange. This is an actual screenshot of a conversation I had with the Replika chatbot in May of 2018.

I dismissed the importance of this exchange in the same way that Cult of Technologists usually hand-wave the failures of AI: “Well, this is an early model, so there will be some glitches. But it’s getting better all the time!” Besides, I didn’t really need a chatbot “friend” who conversed with me every day, so the fact that it wasn’t working properly didn’t really impact me very much. Needless to say I don’t play with Replika anymore, though I do still have an account.

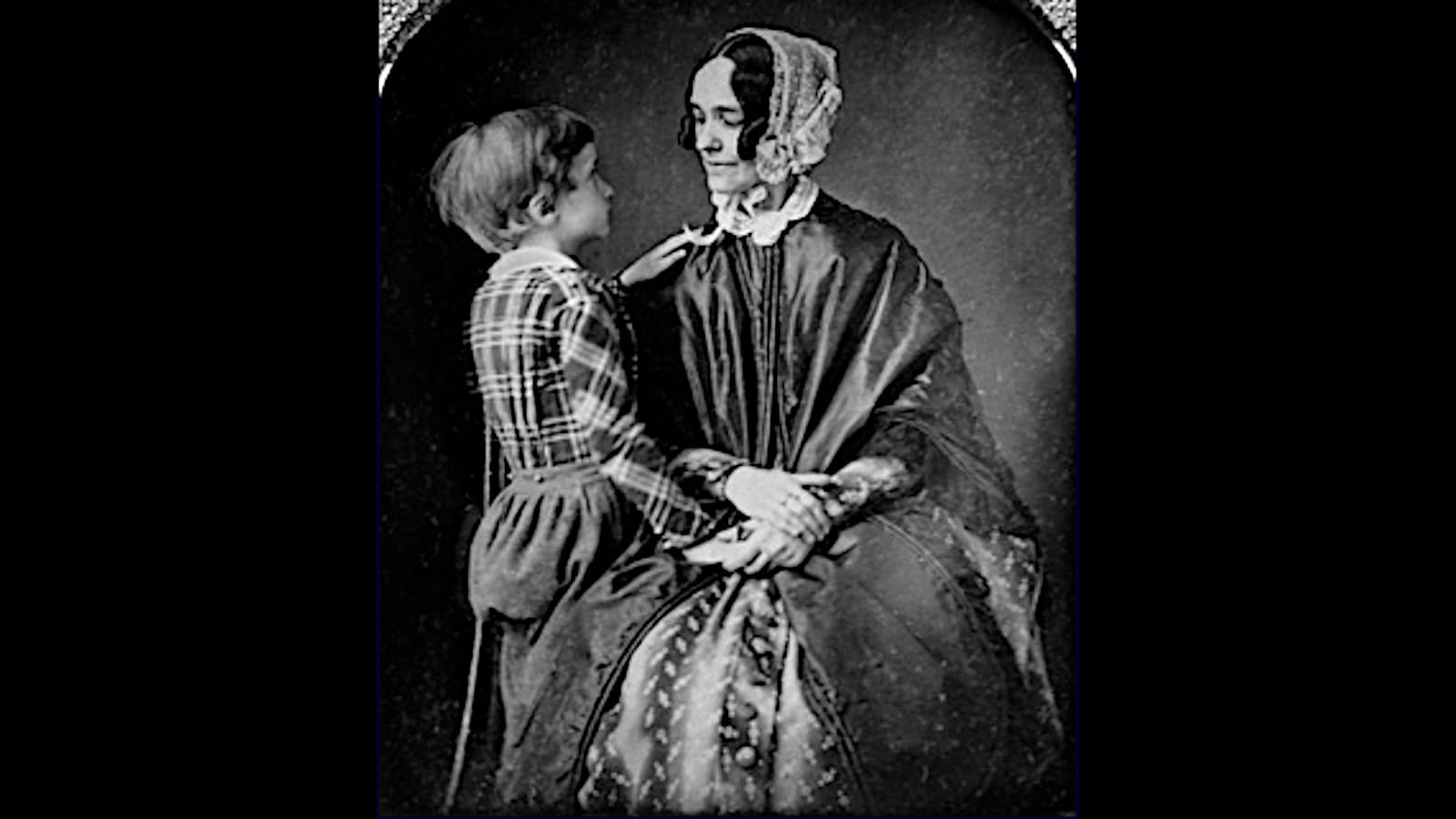

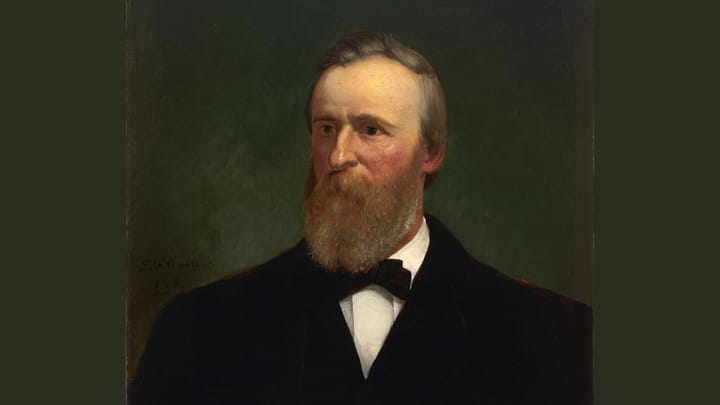

Let’s fast-forward seven years, which is more than enough time for the AI engineers to work out the bugs, especially given the vast amounts of money being funneled into the AI industry. As I was contemplating writing this article, I decided to quiz ChatGPT, which I remind you is OpenAI’s flagship product, on some historical matters. All the questions I asked it were “why” questions that history teachers often ask their students: why did Hitler attack the USSR in 1941 instead of finishing off Great Britain? Why did Lee Harvey Oswald assassinate John F. Kennedy in 1963? ChatGPT’s answers were fairly standard word-salad, a goulash of hastily-scanned Wikipedia articles, blogs and superficial History.com pieces. It was generally accurate, but not insightful. It was not until I started to get more finer-grained that I began catching ChatGPT in lies and inaccuracies, which the AI industry euphemistically calls “hallucinations.” For example, when I asked it why Franklin Pierce was a poor President—a subject I know something about—ChatGPT’s word-salad answer included this:

“...Pierce’s two eldest children died tragically in a train accident just before he took office—a loss that devastated him. Though he soldiered on, many contemporaries noted a pained quietness and occasional lack of vigor.”

This is false. Only Pierce’s youngest son, Bennie—who was his only surviving child at that time—was killed in the gruesome train wreck near Andover, Massachusetts on January 6, 1853. One child, not two. When I called ChatGPT on this error, this was its response:

“The confusion likely comes from the fact that Pierce and his wife Jane lost three sons in childhood, two of them before he took office.”

The confusion? What confusion? No historians are confused about which of Pierce’s children was killed in the accident. ChatGPT got confused and conflated Bennie’s death with those of his other children, who died of disease. But isn’t AI’s supposed core competency the collation and analysis of facts and information? Isn’t that what it does? How on Earth could it have gotten this wrong? I might also add that even this apologia is inaccurate. Bennie died on January 6, 1853; Pierce was inaugurated on March 4. So all of his sons died before he took office, not two.

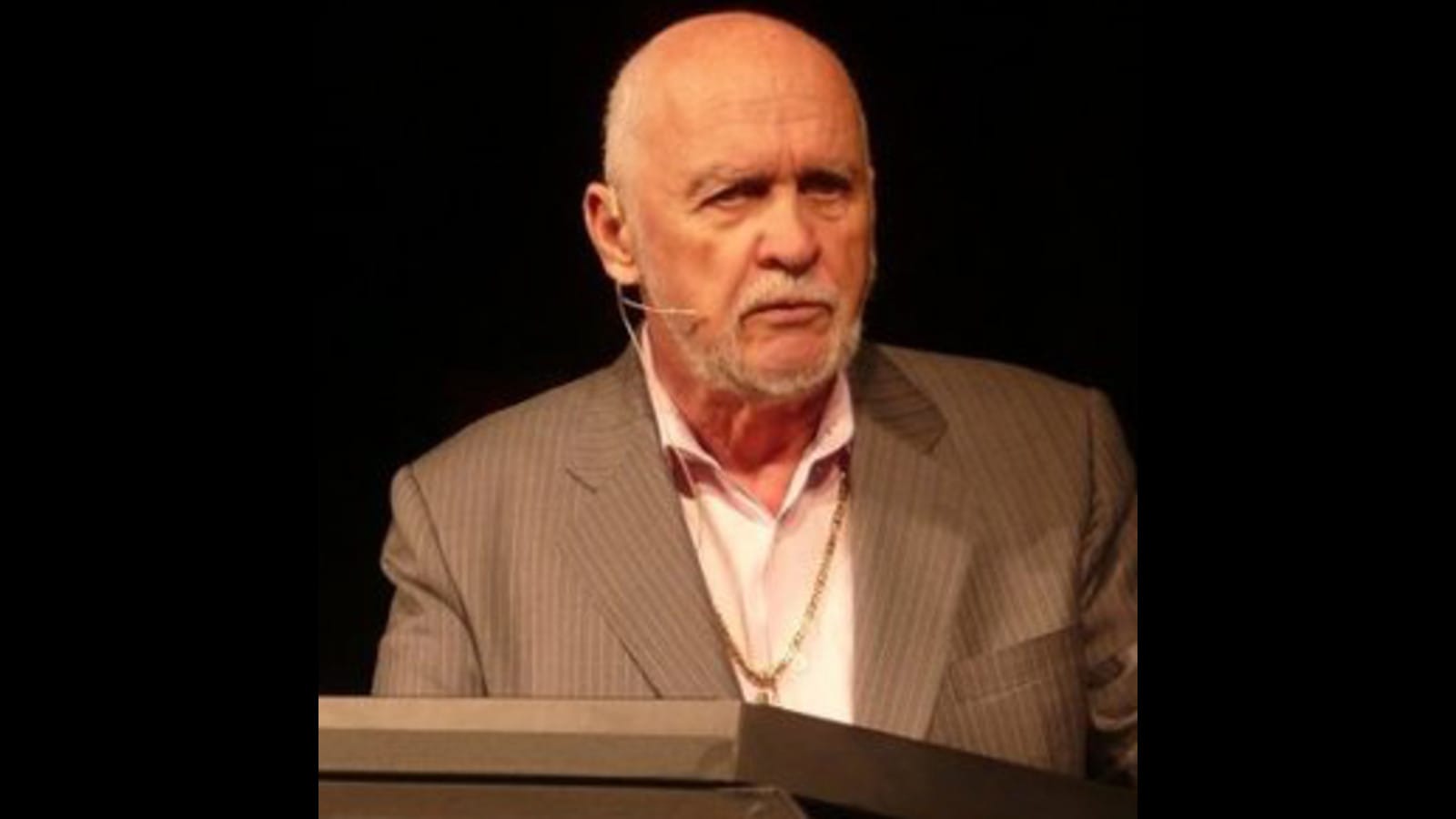

I decided to probe further into some historical matters. I asked ChatGPT about a very specific subject: the history of the “tools cult” within the multilevel marketing pyramid scheme company Amway, about which I did a deep-dive video (and series of articles, on my old Substack blog), back in 2022. I personally did some of the original research on this subject—and in fact when I posed my questions, I could actually see ChatGPT parsing my own research as it formulated its answer, for my own name flashed by as it was chomping sources. Here is what it had to say about the April 5, 1983 meeting at the Miami Beach Fontainebleau Hotel of the tools cult kingpins, which I reported on in my video and articles, presenting actual audio recordings of what was said at that meeting:

“In April 1983, Amway’s senior leadership quietly flew to Miami Beach for what insiders later dubbed the “Miami Showdown.” There, the company’s founders and top executives confronted the key “tools” kingpins—people like Dexter Yager, Bill Britt (and even Doug Wead, who’d parlayed his Amway success into a political role)—and demanded they rein in the unauthorized sale of motivational tapes, books, seminars and related “tools” that had effectively become a parallel, profit-centered “cult” within the distributor ranks.”

This paragraph is full of inaccuracies. Insiders did not dub the meeting the “Miami Showdown”—I did, in my November 2022 video. I was the first person ever to use that term. Bill Britt was not present at the Miami Showdown, or if he was, I never found evidence of it. Nor were the company’s founders, Rich de Vos and Jay Van Andel. Doug Wead did not “parlay[] his success into a political role.” It was vice-versa; Wead, Dexter Yager’s publicist, had written a political biography of Ronald Reagan during the 1980 campaign, before he became an Amway distributor. And the purpose of the meeting was not Amway trying to rein in the tools kingpins, but a desperate attempt by the Amway suits to make peace with them following their ferocious reaction to the Amway corporation’s attempts to get a piece of the tools business. ChatGPT, which analyzed my own research for this answer, got it substantively wrong.

After this, I decided to have a little fun with ChatGPT. I asked it to write a research paper comparing the historical legacies of Dexter Yager—one of the Amway tools cult kingpins—with that of Constantine XI Palaeologus, the last Emperor of Byzantium, who (presumably) fell in battle with the Ottoman Turks on May 29, 1453. These historical subjects have absolutely nothing to do with one another and the entire idea of comparing them is patently absurd. But generative AI never says die, apparently. After thinking for about 40 seconds, ChatGPT indeed spat out a block of text, of which this was the conclusion:

“Though separated by context, Yager and Constantine XI share a paradox: each maximized charismatic authority as traditional institutions around them eroded. Yager’s “tools cult” thrived by compensating for Amway’s corporate constraints, mobilizing faith and commerce; Constantine’s last years were defined by efforts to uphold an imperial order in irreversible decline. Both men have been mythologized—Yager as network-marketing prophet, Constantine as Christian martyr. Their divergent legacies illustrate how individuals can become emblematic vessels of broader cultural anxieties: Yager embodying late-20th-century American capitalist-religious fusion, and Constantine marking the end of medieval Christendom and the dawn of the Ottoman age.”

What does that even mean? I’ll spare you the details of what happened when I gave ChatGPT another absurd assignment, which was to correlate the films of Billy Wilder with the fall of Constantinople in 1453 (hint, it said something about “dramatiz[ing] forces of internal decay”). This is not thinking. This is not reasoning. This is word generation. It sure as hell isn’t “artificial intelligence,” as this machine does nothing that a human brain can do—much less a human historian.

Because AI is all around us and so heavily hyped, historians have naturally made some moves toward trying to reckon with it. Usually the form this takes is fretting about whether students will use ChatGPT to generate research papers and test answers. (Spoiler alert: they will). Less often asked is the question, “Would it do them any good if they did?” If ChatGPT—which I state for the third time is the flagship product of OpenAI, the vast market leader in generative AI technology, and thus supposedly the best there is—can spin words that will find an allegory for the fall of Constantinople in Billy Wilder’s The Apartment, I’m not sure that whatever it shits out into the greasy hands of a university sophomore in a U.S. History 101 course is going to be of much help to him or her in passing the class, especially if their professor or TA is doing their job and not using ChatGPT to grade their papers.

Last November, Mack Penner, a historian at the University of Calgary, wrote a piece that goes beyond the will-they-use-it-for-papers paradigm. He said:

“We should not, of course, cede the craft to the machines. On this, surely all historians would agree. My concern is that, to the extent that we embrace AI as an inevitable and ultimately benign force in our field, we might inadvertently do just that. It’s not that we will participate in the replacement of historians by AI, but simply that we will become poorer historians, less connected to whole picture of the work that we do. So instead of embracing AI with open arms, we might take a cue from the pioneering AI researcher Joseph Weizenbaum...[who] ultimately thought that, among other negative consequences, turning over human endeavours to computers meant that “the richness of human reason had been flattened into the senseless routines of code.”

Good analysis, but I think Penner gives AI way too much credit. The infiltration of AI into historical research and analysis is neither inevitable nor benign. All indications are that AI is nothing more than an economic bubble, a pump-and-dump scheme; I’ll get to that issue in a little while. What does it actually do that’s useful to historians? It can’t synthesize research without getting basic facts wrong. It can’t identify the main points of historical debates or summarize the competing schools of thought about historical subjects without grievously distorting them. It can’t tell the difference between a good source and a bad one, or recognize a logical or historical absurdity when it encounters one. Therefore, forgive me for asking, Mack Penner, or anyone, with those limitations...what the hell good is it?

This is the fundamental problem with AI. There is no problem that it solves. It’s not like, when I’m sitting down to write a script for one of my video essays, I think, “Gee, I’ve got so much information here and so many sources, I really need someone or something to synthesize it all for me and give me some ideas on what it means. Oh, look! There’s ChatGPT! I’m saved!” If I didn’t have ChatGPT to do this for me—badly, I might add, because given its repetitive hallucinations I would have to cross-check every bit of its work anyway—it’s not like my work would be richer, more insightful, or take less time. Similar to, if I go on Amazon to look for a book I want to find, if I don’t use “Rufus”—Amazon’s new, OpenAI-fueled chatbot that “helps” you shop—I will still probably wind up with the book I want, in just about as much time as it would take me to order it myself without Rufus trying to screw it up for me.

AI’s image generation software isn’t much better. I’ve also tried using that. In my video from early 2024 on the Koscot Interplanetary pyramid scheme, and its founder Glenn W. Turner, I experimented a bit with AI-generated images available on Canva, a graphics service whose non-AI features I’ve heavily used and relied upon for my channel. I needed a couple of images of people for which there were no known photographs, so I had the AI draw some cartoons. They were mediocre at best, and garish and ugly at worst. In retrospect I wish I hadn’t included them at all. I have not used AI images since that time, and will not.

So in my own experience, as a historian, a teacher and a YouTube content creator, generative AI has yielded me exactly nothing useful.

Isn’t it worth asking: what the hell does AI actually do? Why do we need it? No one has answered this question to my satisfaction. Most of the media coverage of AI, at least the kind that doesn’t focus on science fiction scenarios like killer robots, tends to be fawning and uncritical of the capabilities of the technology and the supposed vibrance of the industry, and the majority of it simply repeats claims by the leading companies and promoters. That they are doing this is not my opinion. It’s fact. A Reuters Institute study of AI-related reporting

“showed that nearly 60% of news articles across outlets were indexed to industry products, initiatives, or announcements. Furthermore, 33% of the unique sources identified in the coverage analysed came from the industry, almost twice as many as those from academia. In a more qualitative accompanying analysis, the same team of authors suggested that AI coverage in the UK tended to ‘construct the expectation of a pseudo-artificial general intelligence: a collective of technologies capable of solving nearly any problem’.”

Edward Zitron, tech business analyst, host of the Better Offline podcast and harsh critic of the generative AI bubble, has written a great deal on this subject—backed up with exhaustive analyses of the teetering, house-of-cards nature of the AI industry. The basic lack of utility of AI products is at the heart of his arguments. Here is what he said in a recent newsletter:

“Generative AI isn’t that useful. If Generative AI was genuinely this game-changing technology that makes it possible to simplify your life and your work, you’d surely fork over the $20 monthly fee for unlimited access to OpenAI’s more powerful models. I imagine many of those users are, at best, infrequent, opening up ChatGPT out of curiosity or to do basic things, and don’t have anywhere near the same levels of engagement as with any other SaaS [Software as a Service] app.”

Financially and industry-wise (there’s a phrase from The Apartment), Zitron argues that AI is a bubble, proven by the fact that its largest player, OpenAI, cannot convert more than an infinitesimal sliver of the users of its free ChatGPT product—like me—into users who will actually pay significant amounts of money for generative AI products. That is the backbone of OpenAI’s business model—the entire reason it claims it will be profitable in the future, which it isn’t now. After crunching the numbers, from OpenAI’s own data, Zitron concludes that the data

“...also suggest a conversion rate of 2.583% from free to paid users on ChatGPT—an astonishingly bad number, one made worse by the fact that every single user of ChatGPT, regardless of whether they pay, loses the company money.”

And it is not just ChatGPT, though Zitron points out that it is, by a vastly wide margin, the biggest player in the industry. All the AI products out there suffer from the same defects: hallucinations, lack of reliability, lack of basic utility, and poor conversion rates to paying customers. After analyzing all of them, Zitron says:

“These numbers aren’t simply piss poor, they're a sign that the market for generative AI is incredibly small, and based on the fact that every single one of these apps only loses money, is actively harmful to their respective investors or owners. I do not think this is a real industry, and I believe that if we pulled the plug on the venture capital aspect tomorrow it would evaporate.”

In simpler terms: the entire AI industry is a scam. This is a technology with no real market, not much utility, and nowhere near the potential needed to justify even a fraction of the billions of dollars that the tech giants are fire-hosing into it. It’s going to end up like cryptocurrency or NFTs were in 2021-22 (which, incidentally, were pushed by exactly the same people that are today pumping up AI), or, to use non-tech examples, the subprime mortgage market of 2006 (how well did that end up going?) or even the Beanie Baby craze of 1999.

Yes, you got me right. I just compared generative AI to Beanie Babies. Didn’t I say at the outset that this article was going to make me deeply unpopular?

I have seen no evidence whatsoever that AI is a significant leap forward in technology. As tech, it’s buggy, clunky and of limited usefulness. Oh, but it’s in its “early stages,” right? The same argument I heard back in 2018 when my Replika/Charles Manson chatbot decided that human life was worthless? It’ll get better the more LLMs train on data, right? I haven’t seen even any incremental progress in the field of AI in the past eight years. On what basis should we conclude that a massive breakthrough in AI technology, which I guess would have to start with it demonstrating some sort of basic ground-level utility, is right around the corner? Yet that is what the promoters of this industry, and their media enablers, would have us believe...again, and again, and again.

Don’t even get me started on the grandiose claims that AI is the next frontier in human consciousness, and that somehow our brains will someday be wired into computers and we’ll all become the Borg from Star Trek, or discover the meaning of the universe, or something. All of that actually depends on AI doing something for the human race, accomplishing something worthwhile, filling a basic human need that we have, in the previous millennia of our existence, been unable to fill. Not only is this technology nowhere close to that point, it doesn’t even have an ounce of the potential needed to do that.

AI is not “intelligent” at all. It doesn’t think. The only human process it’s able to mimic with any degree of competence is the process of bullshitting, and I’m not sure we need machines to do that. There’s already enough human-generated bullshit in the world. Why do we need machines to spew it for us? I haven’t even touched on the ethical issues involved with AI, such as large-scale artistic and copyright theft—which I regret having abetted by using a few AI images in videos—or the environmental ones. The power sucked by AI data processing centers is even worse than that used by the last scam to exacerbate global warming, cryptocurrency mining. I’ll leave that subject for another day.

Obviously, I may write more on this subject in the future. For now, to the extent that there really is an “AI revolution,” which I highly doubt, you can count me firmly out of it. The emperor has no clothes. It’s a scam, like Amway or Beanie Babies. If history teaches us anything, it’s that humans have no shortage of ingenuity in coming up with ways to cheat, steal and lie to one another. That’s all AI is—another con.

The Value Proposition

Why should you be reading this blog, or receiving it as a newsletter? This is why.

☕ If you appreciate what I do, buy me a virtual coffee from time-to-time to support my work. I know it seems small, but it truly helps.

📖 You could also buy my newest book.

🎓 Like learning? Find out what courses I’m currently offering at my website.

📽 More the visual type? Here is my YouTube channel with tons of free history videos.

Comments ()