Disaster in memory: the Great Blizzard of 1975.

49 years ago this week, Midwesterners suffered the "blizzard of the century." How we remember weather events of the past matters.

In the first third of January 1975, some 49 years ago this week, one of the great storms in recent American history descended upon the American Midwest. The event began out over the Pacific Ocean on January 8. The Pacific disturbance, once it moved over the Rocky Mountains, collided with another disturbance which meteorologists call a “Panhandle Hook.” As often happens when a mass of cold air meets a mass of warmer air, atmospheric violence ensues. There was a lot of it in this case. The storm spawned thunderstorms and eventually tornadoes in Texas, Louisiana and other parts of the South which killed 12 people. In the more northerly part of the Midwest, the storm manifested itself as record low barometer readings, biting winds, and lots and lots of snow. When recounted like this, a bland series of scientific, geographic and meteorological events, the Blizzard of 1975 sounds like a footnote to history, at best. In reality it etched its way deep into the memories of generations of Midwesterners--and the imaginations of more.

I didn't witness this event. For one thing, I was barely 2 years old, and my family, which was military, was living in Texas (?) at that time. But I spent part of my later childhood in Omaha, Nebraska, a place where the weather is often threatening--tornadoes particularly, but savage blizzards and cold weather events aren't uncommon. I credit my childhood years in Omaha with sparking my awareness of weather that led, indirectly, to what I began studying as a historian: I ultimately did my dissertation on climate and weather events known most prominently as the "Year Without Summer" of 1816. Extreme weather events, particularly snow, also figure prominently in my memory and imagination. Not long ago I wrote for this blog a reminiscence of my own strangest Christmas (2008), disrupted by an unusual snow event in Portland, Oregon. So I'm fascinated by stories of blizzards long past and how people experienced them, and how they continue to live again, in memory and retellings, as time stretches on.

In Omaha, and many other places, the first snow started falling on January 10 and never let up. People caught out on the broad Nebraska freeways in the storm described it as a “wall of white” moving toward them, unlike anything, even people who’d lived in the area for many years, had ever seen. People around the region were already suffering “blizzard fatigue.” A few days earlier weather stations had warned of heavy snows which didn’t materialize, so businesses and schools were less apt than perhaps they would otherwise have been to close and send their people home this time. Nonetheless, once snow starting dumping, many businesses let their people go at 3PM. For many who managed to drive home on slick roads, this was the last time they would be outside for days.

As quickly happens in extreme weather situations, urban infrastructure was badly hit. Power lines, overburdened by snow, started to go down, knocking out electricity for thousands of households. For many, power would be off for three days. One Omaha resident reminisced, writing in 2009, that during the 1975 storm he and his family huddled in their house, sleeping with their clothes on to keep warm, and ate cold peaches from a can. More than a foot of snow fell in Omaha, and that total was easily equalled or exceeded in other places.

The storm was especially disastrous for livestock. Here is an account by a Minnesota rancher, describing the effect on local cattle (taken from reminiscences about the storm published here).

On the third day the weather broke. The cow herd was missing. Neighbor LeRoy Bush to the west of us had cattle missing, too. They had drifted in with ours and continued to the southeast with our cattle. By late morning, Leroy and his son, Allen, came down on horseback. Setting out on foot with the horsemen, I had no idea what we were about to witness. About a quarter mile from the farmstead we saw dead cows laying here and there. Many of the live cows had so much snow and frost on their eyes and noses they could not see, and some had already suffocated. You could walk up to some of them and grab the chunks of ice and pull it off of them. We found a number of dead cows stuck in the snow on either side of the fence as they tried to jump the fence and couldn’t make it because of the deep snow. Five cows went down on the ice below the bridge on the east road. It was May before we could get their carcasses pulled out. We drove the live cattle eastward in a jagged pattern where the snowdrifts would allow us to herd the cattle, cutting fences wherever we could. We moved the cattle to the Reiny and Doris Henrichs farm. We overnighted the cattle there.

A resident of South Dakota recalled (here):

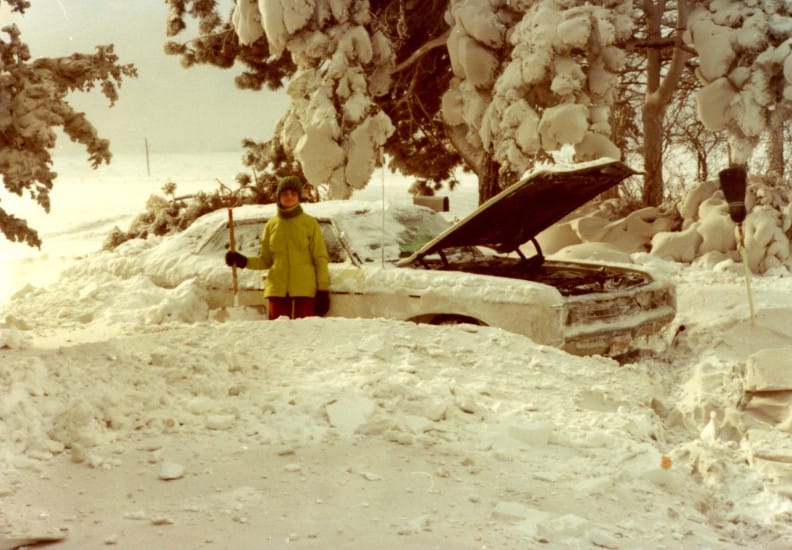

The wind hurtled and howled around our little house all night; the power flickered once or twice, and the temperature plunged to more than -20 by morning. The next day, we were going to free Kathy’s car but for two things: we couldn’t see it under the snow and fallen branches and we couldn’t open the front door. Honey’s brother being in Texas at furniture market and we being in charge of his teenagers, we called the house and asked Kevin, the oldest, to come over on the snowmobile with a shovel and dig his way in. “We’ll feed you. Eggs ok?”

That snow barely fit the definition of snow. It was grey, mixed with South Dakota dirt and beaten into the consistency of talcum powder. It packed tight, deep, and high. Drifts exceeded 12 feet in some areas. And it stuck around for a long, long time. Somehow tunnels were cut through the snow creating canyons and we drove to and from work on cobblestone of packed snow/ice for more than a week until it wore smooth.

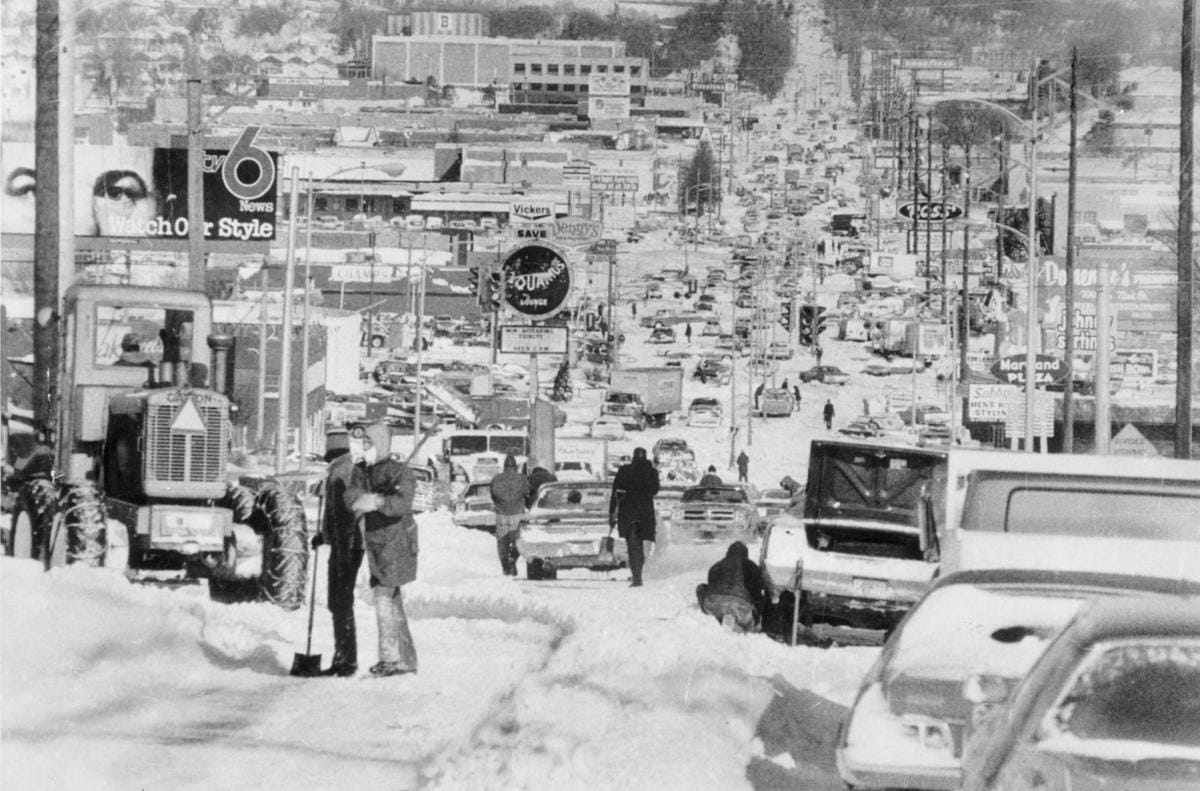

Stories of rescues or supply deliveries by snowmobile are common from this storm. At its height, and in the aftermath, it was the only reliable way to get around. In the 1980s I recall seeing a reprint of a famous picture taken by the Omaha World-Herald of 72nd Street, Omaha’s main drag, in the aftermath of the storm. The picture was taken with a telephoto lens and shows hundreds of cars utterly buried and the signs of the city’s retail establishments sticking up out of a mantle of white. I never forgot that photo. A reproduction of it serves as the header image of this article. If the photo is something that lingers so prominently in my memory after 40 years, I can only imagine what the reality must have been like.

Recovery from a storm like this takes weeks, if not months. At least in the case of Omaha, the memory of the great blizzard was still very fresh in their minds when, in the spring, the city suffered its greatest-ever natural disaster: the great tornado of May 6, 1975, which tore the heart out of the city. Extreme weather seldom occurs in isolation. The Great Blizzard of 1975 is still fondly–and coldly–remembered, now nearly 50 years on.

The Value Proposition

Why should you be reading this blog, or receiving it as a newsletter? This is why.

☕ If you appreciate what I do, buy me a virtual coffee from time-to-time to support my work. I know it seems small, but it truly helps.

📖 You could also buy my newest book.

🎓 Like learning? Find out what courses I’m currently offering at my website.

📽 More the visual type? Here is my YouTube channel with tons of free history videos.

Comments ()