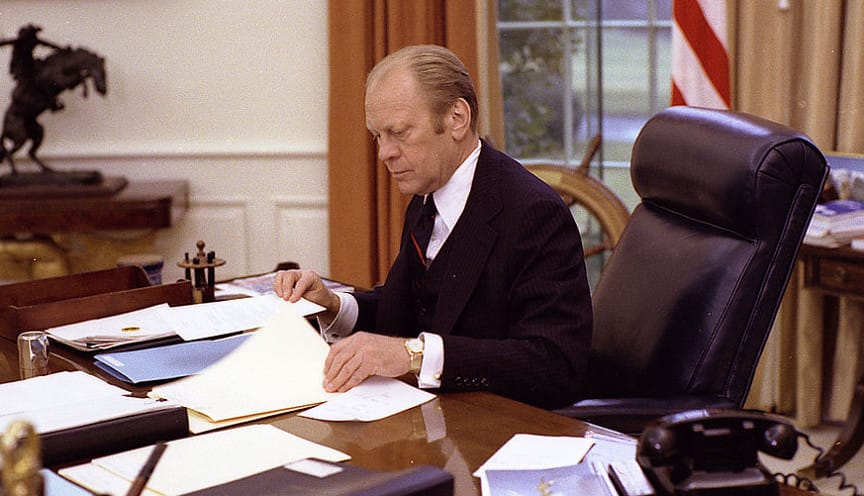

Corruption or mercy? The Ford Watergate pardon.

Why did Gerald Ford pardon Richard Nixon after Watergate? Was it an act of cronyism, or moral and political wisdom?

Fifty-one years ago tomorrow, on September 8, 1974, President Gerald R. Ford issued Proclamation 4311, which by its terms granted “a full, free, and absolute pardon unto Richard Nixon for all offenses against the United States which he, Richard Nixon, has committed or may have committed or taken part in during the period from January 20, 1969 through August 9, 1974.” Ford had been President for one day short of a month, having taken over after Nixon’s resignation as he faced certain impeachment. The pardon essentially ended the Watergate affair, at least so far as it concerned Nixon. It was a bombshell, one that exploded over the country and rankled great partisan feelings. Historians have judged it to be the central event in Ford’s truncated Presidency, and possibly the reason why he couldn’t win election in his own right in 1976. It was also, if you asked Ford, a fairly easy decision, and one that he remained proud of until the end of his life in 2006. The pardon is destined to be mentioned on the last page of almost every book about Watergate written until the end of the Republic.

It’s a decision worth examining, both historically and morally—and especially so given the tumult and corruption of the Trump era. Much of the country was outraged when Ford announced the pardon. The New York Times called it unwise and unjust. Teddy Kennedy, the de facto Democratic leader in the Senate, was also extremely critical. Public opinion polls shifted against Ford at the shaky outset of his crisis-riddled Presidency. At the time, although Nixon had resigned he was still deep in Watergate-related legal matters, as were numerous others who had taken part in the scandal to break into the Democratic Headquarters in 1972 and then cover it up. (I did a video on Watergate, by the way). It was quite possible and in fact even likely that Nixon would be charged with a federal crime—most likely obstruction of justice, Nixon’s commission of which was captured on tape—and have to undergo a trial. That trial would likely have been the most costly and acrimonious legal proceeding in American history up to that point. Assuming appeals, which might have dragged on for years, the question of whether “Tricky Dick” would go to jail might still have been an open one as late as 1980, two Presidential elections after his resignation. If that happened, the Watergate affair would have consumed the oxygen of the nation’s political life for nearly the entire decade of the 1970s.